Black Lives Matter at School Marketplace of Learning

Bruce-Monroe at Park View 2025

By Tamyka Morant

Introduction

Our school’s participation in the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action began in 2018, when a small group of teachers first engaged students in learning around the principles. By 2019, the work expanded into a schoolwide effort. During that year, we attempted to address all of the principles within a single week. While the experience was meaningful, we quickly realized that the depth of inquiry required for students to truly understand the principles could not be achieved within such a short period of time.

In response, we shifted from a week-long event to a quarter-long interdisciplinary study. By 2021, this evolution resulted in the development of a schoolwide scope and sequence designed to intentionally engage students in sustained, developmentally appropriate study of the Black Lives Matter at School principles from early childhood (three-year-olds) through fifth grade.

Each grade level now engages in a deep study of one principle through interdisciplinary units lasting six to ten weeks. These units center inquiry, identity development, critical thinking, and collective action, allowing students to revisit essential ideas over time with increasing complexity and independence. Students unpack the meaning of their principle, engage with literature, art, mathematics, history, and contemporary examples, and ultimately design action projects that demonstrate how they live the principle in their own lives and communities.

The design of the scope and sequence ensures that by the time students graduate from fifth grade, they have engaged in deep, sustained study of at least seven of the principles. In this way, students revisit core ideas across multiple years and contexts, allowing their understanding to deepen as they grow academically and developmentally.

The culmination of this work is the Black Lives Matter at School Marketplace of Learning, framed as a Celebration of Learning day. During this event, each class showcases its learning through exhibitions and interactive presentations. Students visit other grade-level exhibits as a class, like an in-school field trip, studying how other principles are understood and enacted across the school community. They participate in structured reflection protocols that invite them to learn from the work, perspectives, and experiences of other grade levels, reinforcing the understanding that this learning is both individual and collective. Through guided reflection activities and a culminating survey, students synthesize what they learned about their own principle as well as the principles explored by their peers.

In the evening, families and community members are invited to experience the student exhibitions. Visitors gain insight into both what students learned and how the school approaches teaching, inquiry, and community responsibility. The day concludes with a shared meal, where students, families, and educators celebrate student learning and collective accomplishment together.

Black Lives Matter Plaza Mural

After the Black Lives Matter street mural in Washington, D.C., was removed in 2025 following political pressure and threats to withhold federal funding, students and staff created their own Black Lives Matter mural on school grounds as an act or reflection and protest. The mural affirmed the school community’s commitment to the principles students had been studying. They ensured that the message would remain visible within their shared space.

Early Childhood: Diversity

Early Childhood (3-4 year olds) engaged in a sustained study of the BLM@S principle Diversity, exploring what it means for people, cultures, and ideas to coexist within a shared community. Through read-alouds, conversations, and guided inquiry, students developed an understanding of diversity as inclusion, empathy, and ensuring that everyone feels welcome, valued, and respected.

Students connected their study of diversity to the design of communities by studying the work and influence of Black architects, including Norma Sklarek, Philip Freelon, and J. Max Bond Jr., and they explored how architecture shapes public experience. They studied the design of communities by examining buildings, schools, and public spaces. Through the creation of a collaborative city model, students explored how communities can be intentionally built to reflect fairness and belonging. Their city includes schools, universities, and shared spaces designed to serve everyone, reflecting students’ ideas that communities should provide opportunities for all people to learn, work, and live together.

Students recreated important buildings, including the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, using these examples to understand how representation and cultural identity can be reflected in public design. Their learning also included an introduction to HBCUs, helping students connect diversity to educational opportunity and community history.

Students further grounded their learning in local history by studying community advocacy connected to their own school, learning about family organizing efforts to preserve Bruce-Monroe at Park View as a dual language school. Through interviews and reflections, students began to understand that communities are shaped not only by buildings, but by different people working together to care for and project shared spaces.

Throughout the project, student thinking was documented through drawings, reflections, and bilingual discussions, supported by collaboration with community members, including the librarian who helped students consider how diversity influences the construction of public spaces. By the end of the unit, students articulated diversity as engaging with others with respect and love, celebrating differences, and ensuring that everyone feels important and included within the community.

The Early Childhood exhibition demonstrated how even the youngest learners can engage deeply with complex social ideas when learning is grounded in inquiry, creativity, and collective meaning-making, while remaining aligned to grade-level developmental and academic standards.

Kindergarten: Black Villages

Kindergarten students engaged in a deep study of one of the newer, revised Black Lives Matter at School principles, Black Villages, exploring how families and communities work together to support and care for one another. The unit began with students unpacking the meaning of family by reflecting on their own experiences, identifying who is part of their family, how families grow and change, and why families are important. Through writing, drawing, and discussion, students described family as “the people who take care of you” and began to understand that family can grow and change over time.

Building from this foundation, students explored the idea of a village as an expanded form of family. They studied the core ideas of Black villages, helpers, sharing and caring, and strong community, and examined the difference between individualism and collectivism. As students reflected on these ideas, many identified that working together “makes the work lighter” and helps everyone succeed. Students discussed the strengths and challenges of both approaches and began to recognize how cooperation supports community well-being.

Students then explored who makes up their own Black village, making connections to intergenerational relationships and recognizing the roles of family members, educators, neighbors, and community helpers. This understanding was expressed through individual village dioramas that represented the people and places important to them and demonstrated how care and responsibility are shared across a community.

As the unit progressed, students applied their learning to their own school and world, considering how to live the Black Village principle at Bruce-Monroe at Park View. During the exhibition, students shared ideas such as “add more Black people,” “make sure everyone is included,” and “make sure we’re not being racist,” demonstrating an emerging understanding of inclusion, representation, and collective responsibility.

The Kindergarten exhibition showed how young learners can engage meaningfully with complex social ideas when given time, language, and opportunities for reflection. Through inquiry, collaboration, and creative expression, students demonstrated that strong communities are built through shared care, inclusion, and a commitment to supporting one another.

First Grade: Intergenerational

First grade students engaged in a deep study of the Black Lives Matter at School principle of Intergenerational, exploring how people of different ages learn from one another and work together to build stronger communities. Through literature, inquiry, and community engagement, students examined how stories, knowledge, and traditions are passed from one generation to the next.

Students grounded their learning in the texts Belle, the Last Mule at Gee’s Bend and The Patchwork Quilt, using quilting as a metaphor for intergenerational connection, memory, and shared experience. They also studied Cassie’s Word Quilt, exploring how stories and words can preserve history and communicate ideas across time. Inspired by these texts, students created their own quilt representations, illustrating what they would pass down to future generations and how their ideas and experiences contribute to a larger collective story.

The unit centered literacy and writing standards, guided by the essential questions: How does learning about the history and experiences of older generations help us understand our world today? How does learning about the experiences of young people help us understand leadership, and how can people of all ages work together to make the world fair and kind? Through writing and reflection, students described the ways they already engage in intergenerational relationships, such as playing, learning, talking, and spending time with family members and elders, and they began to recognize how care and knowledge flow across generations.

A central component of the study was students’ partnership with a nearby senior living center. Seniors visited the school to view the exhibition, and students conducted interviews to learn about their experiences, including conversations about ageism and the challenges older adults sometimes face. Through these interviews, students practiced listening, questioning, and empathy, developing an understanding that leadership and wisdom exist across all ages.

The First Grade exhibition demonstrated students’ growing understanding that intergenerationalism means valuing both younger and older voices, caring for people across age groups, and recognizing that communities are strengthened when generations learn from one another. Through quilting, storytelling, and dialogue with elders, students came to see themselves as part of an ongoing community story that connects past, present, and future.

Second Grade: Loving Engagement

Second grade students engaged in a deep study of the Black Lives Matter at School principle of Loving Engagement, exploring how empathy, community care, and collective action can transform relationships and communities. The unit began with students unpacking the principle through mentor texts including Each Kindness, I Walk with Vanessa, Last Stop on Market Street, and Sit-In. Through these stories, students examined how both fictional and historical figures demonstrated loving engagement by standing up for others, repairing harm, and working toward fairness and justice.

Through shared reading, primary source materials, and recorded interviews, students gathered vocabulary and ideas to describe what it means to take a stand rooted in empathy and community responsibility. Together, they engaged in shared writing to explain their thinking, reflecting on themes of liberation, peace, anti-racism, and the importance of building and transforming relationships. Students considered how loving engagement requires working together as agents of change within their communities.

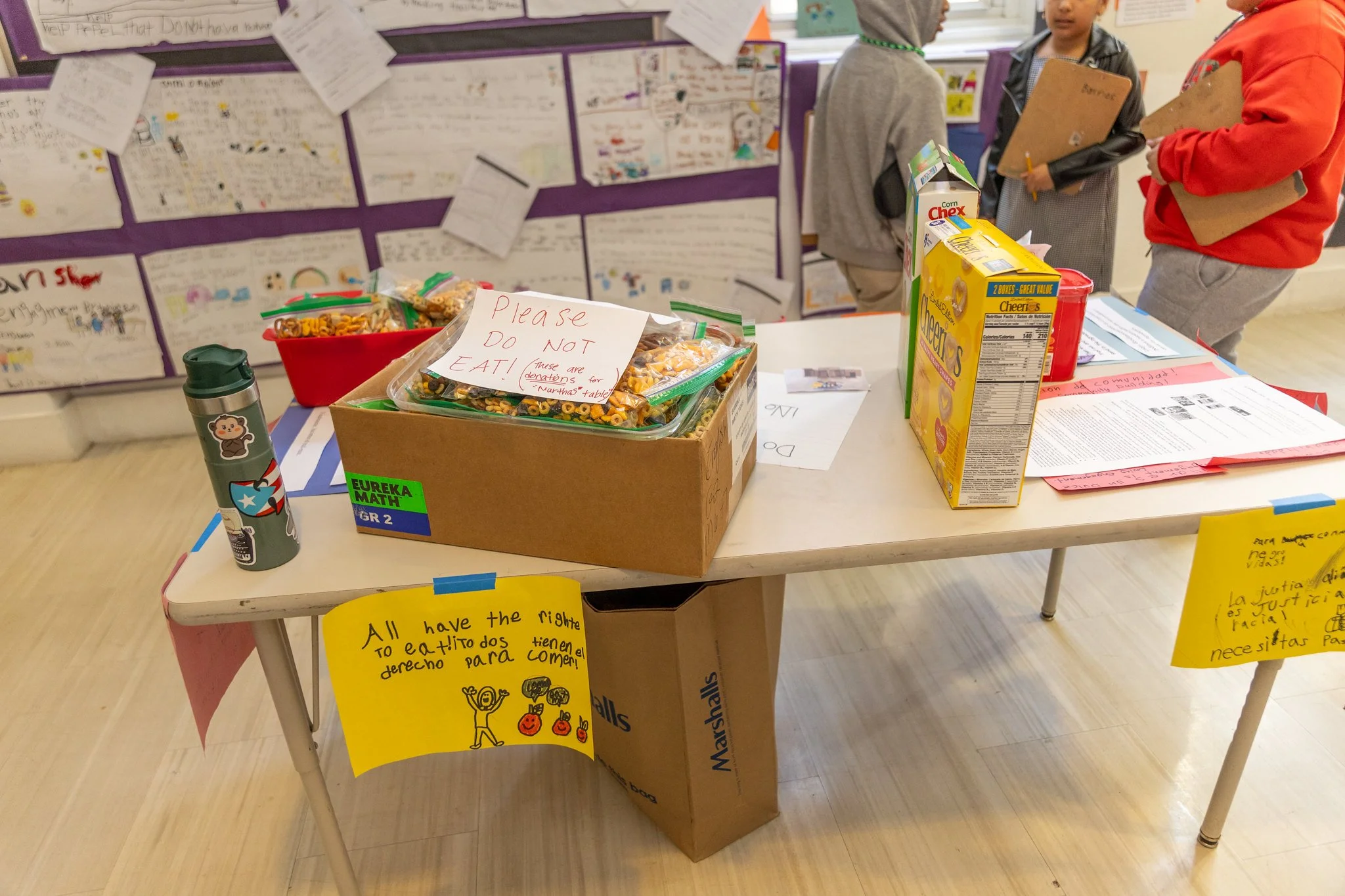

Inspired by the example of the Greensboro Four, students then brainstormed ways they could demonstrate loving engagement in their own lives. Each student developed an opinion narrative in which they made a claim about the best way their class could take action and supported their reasoning with evidence from their learning. These opinion pieces functioned both as literacy work and as a democratic decision-making process, with students’ writing serving as votes for a collective action project.

The class ultimately chose to create trail mix bags for Martha’s Table as their Take Action Project. Working together with family contributions, students prepared 300 bags of trail mix as an act of service grounded in their understanding of loving engagement. Students explained their choice by connecting the project to community care and food justice, noting that providing food supports people experiencing hunger and helps build a more peaceful and equitable community. One student reflected that “trail mix is like integration — it is not just one kind of snack; it’s all together and better that way,” demonstrating how students connected their learning about diversity, cooperation, and justice to their action.

The Second Grade exhibition demonstrated that loving engagement extends beyond kindness as an individual act; it involves taking thoughtful action, working collectively, and recognizing one’s responsibility to contribute to the well-being of others. Through reading, writing, and community action, students showed an emerging understanding of how empathy and collaboration can support liberation and positive change.

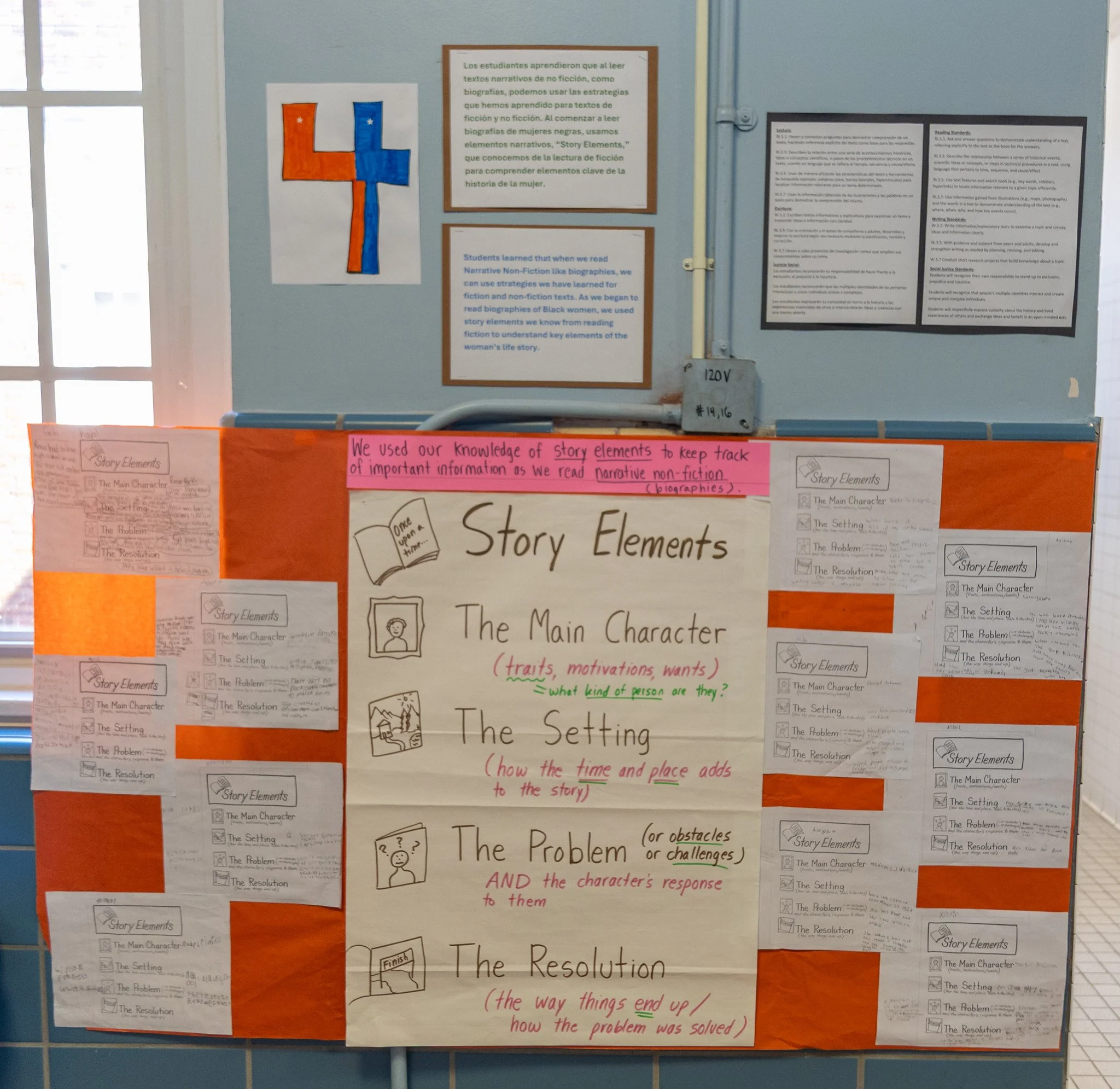

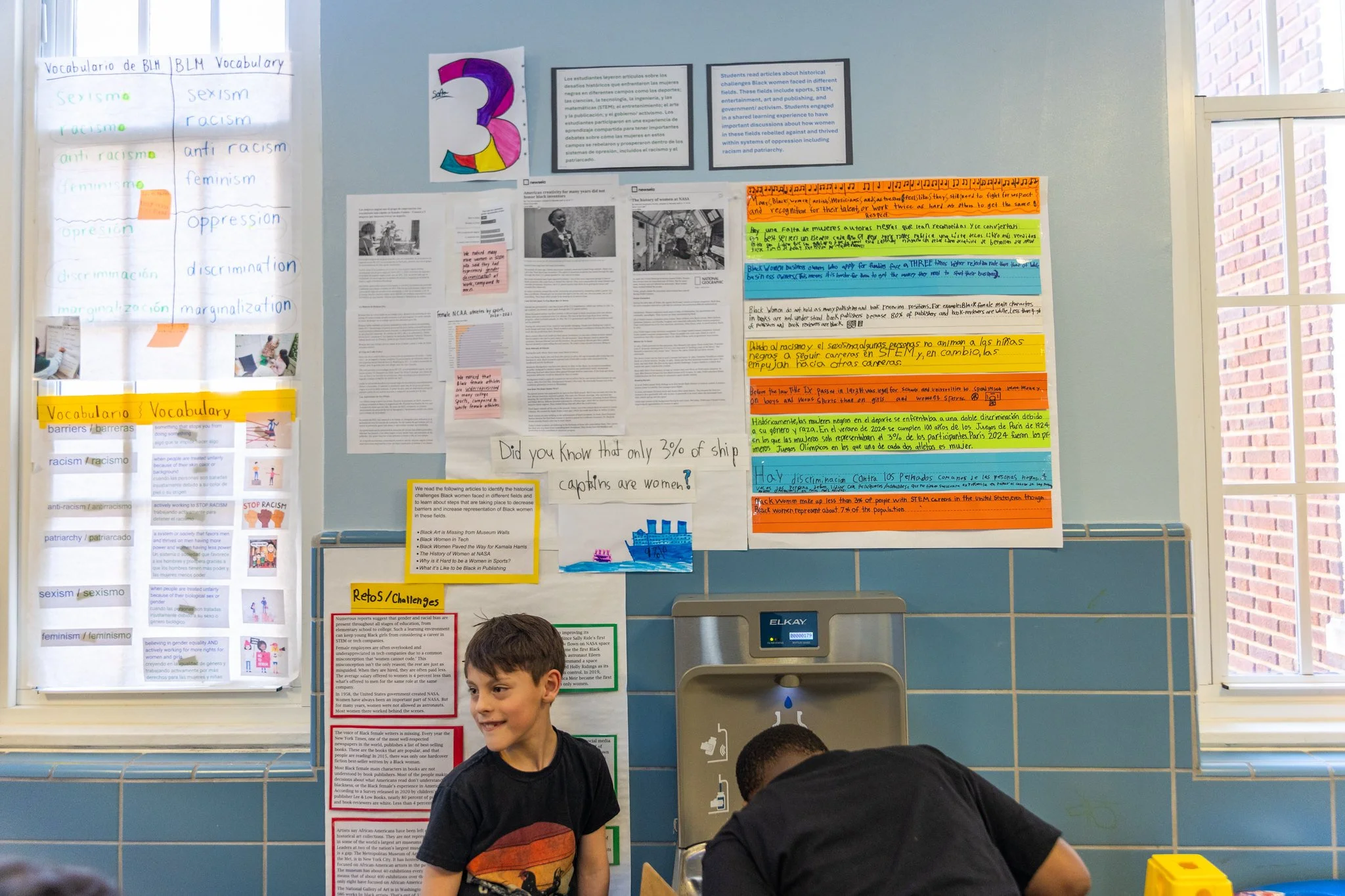

Third Grade: Black Women

Third grade students engaged in a deep study of the Black Lives Matter at School principle of Black Women, examining how Black women have resisted and thrived within systems of oppression and what their leadership teaches us about antiracist action and social change. The unit began with students unpacking the principle through vocabulary study, developing shared understanding of concepts such as patriarchy, racism, sexism, and antiracism. Through discussion and analysis, students explored what it means to recognize and uplift the contributions of Black women in history and in contemporary society.

Guided by essential questions — How do Black women rebel against and thrive within systems of oppression? What can we learn from Black women leaders about being antiracist agents of change? — students began their inquiry by conducting a data investigation. Students completed an inventory of biographies in both the school library and local D.C. public libraries, analyzing how frequently Black women were represented compared to men and non-Black women. Students were surprised to discover the significant underrepresentation of Black women in biographies and used this data to identify a problem within their own learning environment.

As one student explained, “In the public libraries, there are 25,257 biographies of men, 4,239 biographies of women that are not Black, and 1,209 biographies of Black women . . . . Our call to action is to bring awareness that there needs to be more books published about Black women and with Black characters.” Through this analysis, students connected literacy, representation, and equity, recognizing how access to stories shapes what communities learn and value.

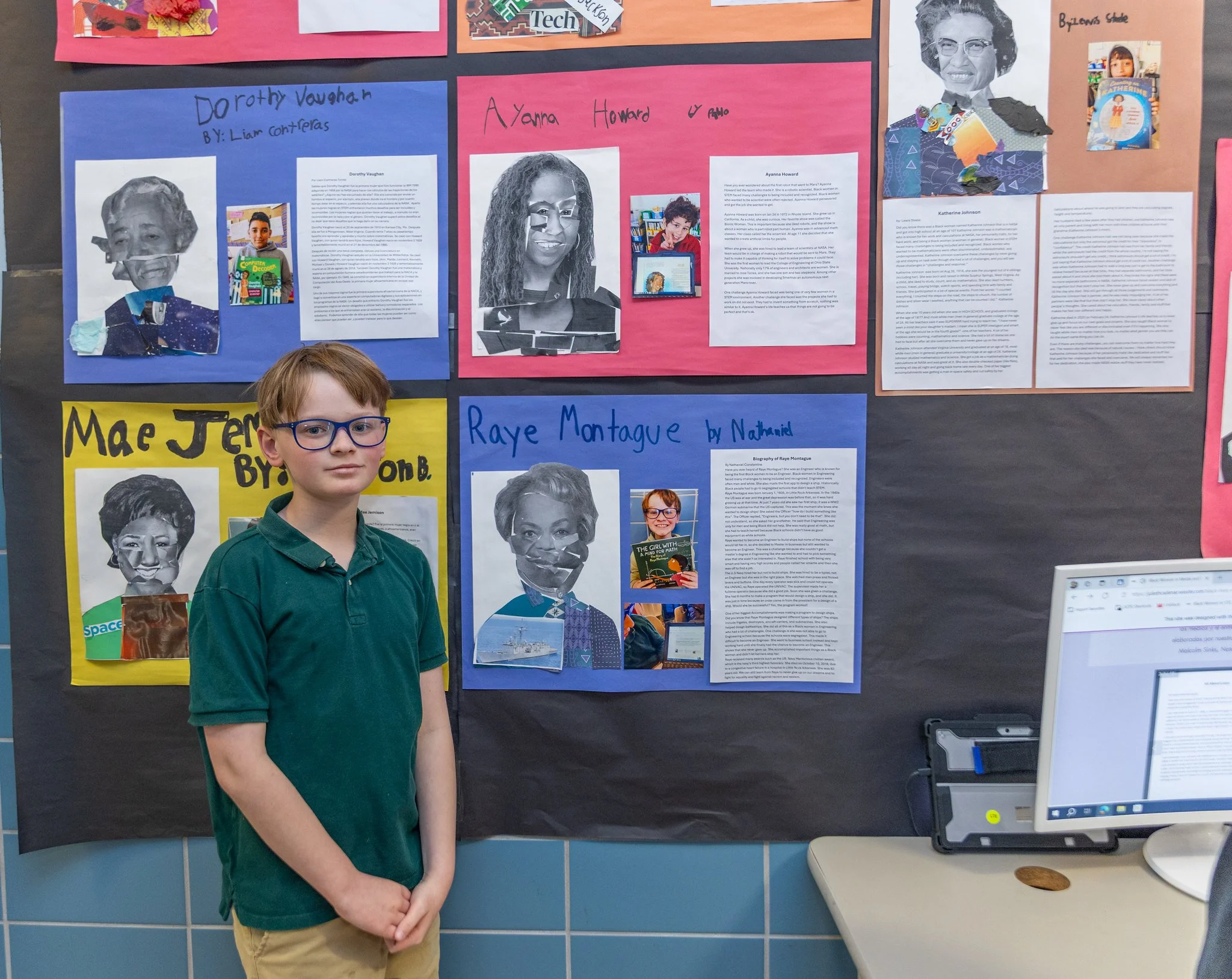

Building on this foundation, students studied nonfiction text structures and conducted research on Black women across fields, including sports, STEM, entertainment, art, publishing, government, and activism. Through note-taking and research strategies, students examined the challenges these women faced and analyzed how they challenged racism and patriarchy while creating pathways for others. Students intentionally selected both well-known and underrepresented figures, including athletes, scientists, artists, and activists, demonstrating a commitment to uncovering stories often absent from traditional biographies.

Each student then authored a biography accompanied by an original artistic representation of their chosen figure. These biographies became part of a collective Take Action Project: a published class book and digital website designed to increase representation of Black women in the school’s library collection. The books, written in English and Spanish, were added to the school library so that future students have greater access to stories of Black women’s contributions and leadership.

As one student shared, “We thought that Black women didn’t get enough biographies in Spanish and English, so everyone chose their own Black woman and we wrote a short biography about them.” Another student described researching artist Paula Mans, explaining the challenges she faced with sexism and single parenthood and how she continued to pursue her work despite those barriers. Nathaniel, who researched engineer Raye Montague, explained how she became the first Black woman to design a U.S. Navy ship and overcame barriers in a male-dominated field, reflecting students’ growing understanding of perseverance, innovation, and representation.

The Third Grade exhibition demonstrated how students can use vocabulary, data, research, and writing as tools for social analysis and action. Through their study, students came to understand that uplifting the stories of Black women is both an academic and community responsibility and that learning can be used to challenge inequity and expand representation for others. In recognition of their work, students’ bilingual anthologies were published in hardback form and placed not only in the school library but also in the library at the National Gallery of Art, extending the reach and impact of their Take Action project beyond the classroom community.

Fourth Grade: Restorative and Transformative Justice

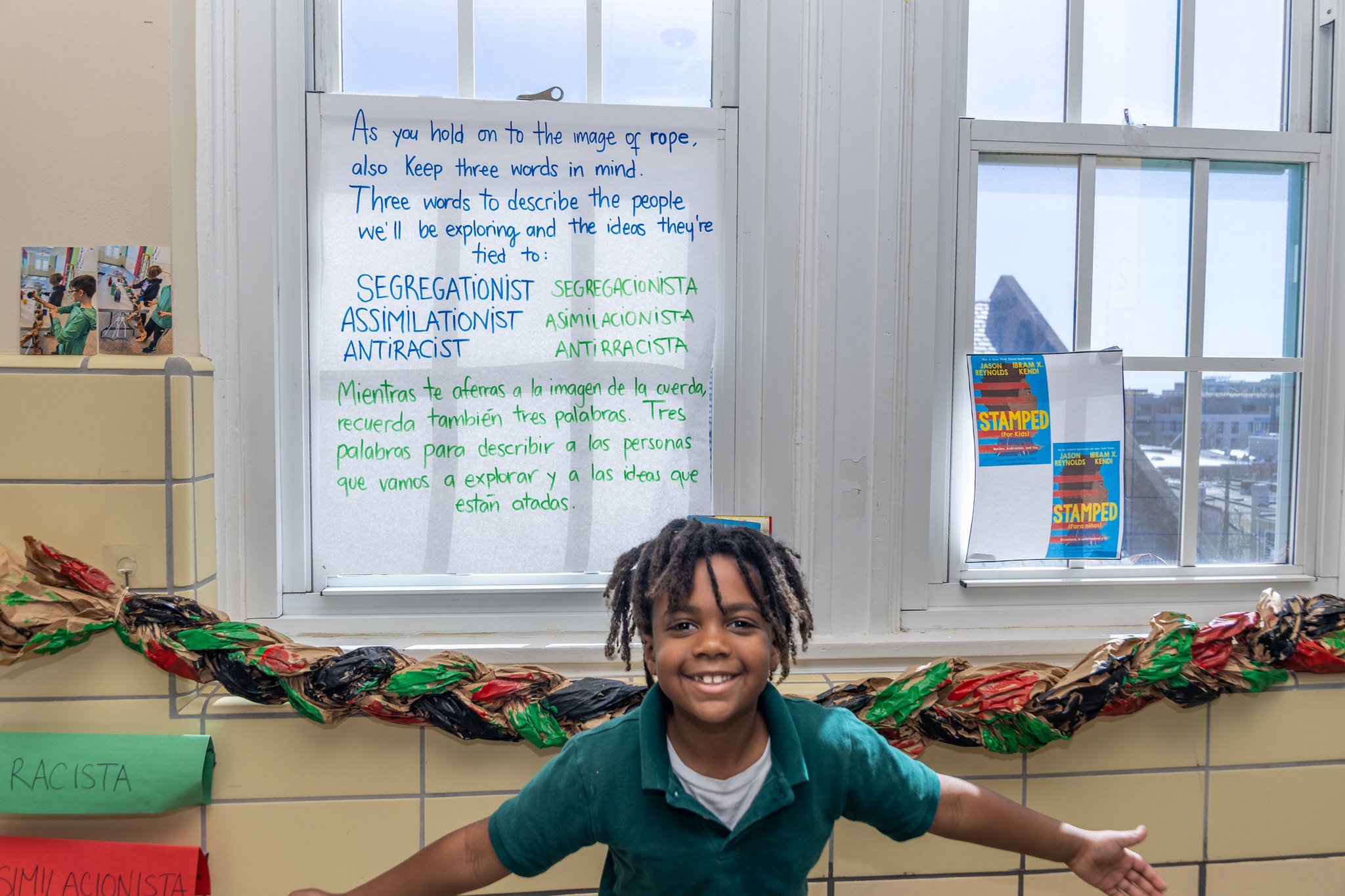

Fourth grade students engaged in a deep study of the Black Lives Matter at School principles of Restorative Justice and Transformative Justice, examining how communities address harm, take responsibility, and work toward repair and systemic change. Guided by the essential question, How do historical themes in Stamped (for Kids): Racism, Antiracism, and You connect to restorative and transformative justice, and how can we use digital media to educate others about these ideas? students explored how justice has been understood and practiced across historical and contemporary contexts.

Students began by unpacking key concepts such as repair, responsibility, respect, and accountability, distinguishing between punitive, restorative, and transformative approaches to justice. Through collaborative discussions and structured meetings, students developed shared definitions and applied these ideas to historical examples studied in Stamped (for Kids). Using a jigsaw structure, students became experts on individual chapters, creating written summaries and digital presentations in which they narrated their learning for peers, demonstrating both comprehension and teaching responsibility.

The unit integrated multiple content areas. In mathematics, students created two-step word problems connected to historical themes, including the study of quilts as coded maps during the Underground Railroad, combining historical context with problem solving and reasoning. In literacy and social studies, students analyzed how racism and bias have appeared in media and advertising, studying examples of discriminatory marketing and redesigning advertisements to reflect dignity, affirmation, and accurate representation. One reimagined advertisement transformed a historically racist image into a message affirming that Black children are “amazing and enough,” demonstrating students’ understanding of how media can either reinforce or challenge oppressive narratives.

Students also examined historical figures through the lens of justice, writing letters from the perspectives of individuals such as Langston Hughes, Ida B. Wells, and Booker T. Washington. These letters required students to analyze accomplishments, challenges, and the ways these figures engaged in resistance and repair within unjust systems. As one student explained, part of the work involved defining punitive, restorative, and transformative justice and applying those ideas to historical narratives.

As part of their digital media work, students created video presentations and a student-led talk show interviewing scholars from Howard University about the historical purpose and ongoing importance of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), extending their learning beyond the classroom and positioning themselves as educators for a broader audience.

The Fourth Grade exhibition demonstrated students’ growing ability to analyze systems of harm and imagine alternatives rooted in repair, responsibility, and collective well-being. Through historical analysis, mathematics, media critique, and digital storytelling, students showed that justice involves both understanding the past and actively working to transform the future.

Fifth Grade: Collective Value

Fifth grade students engaged in a deep study of the Black Lives Matter at School principle of Collective Value, examining how communities work together to address injustice by centering and amplifying Black voices. The unit focused on helping students understand advocacy as both a historical and contemporary practice, grounded in the belief that collective action can bring awareness to community needs and promote meaningful change.

Students began by identifying issues they believed required greater public attention, including food insecurity, access to mental health support in schools, mental health support for LGBTQ+ individuals, and equitable access to STEM education. Through discussion and research, students explored how certain concerns become marginalized or ignored and considered how advocacy can disrupt the silencing and erasure of Black voices while elevating community needs.

Drawing inspiration from Black historical figures and movements, such as James Baldwin, Nannie Helen Burroughs, Fannie Lou Hamer, and the Black Panther Party, students analyzed how activists organized, communicated their ideas, and mobilized communities around shared goals. These historical examples informed students’ own advocacy work, helping them consider questions such as: How do we organize thoughtfully to center Black voices in our advocacy? and What inspiration can we take from the experiences of Black anti-racist activists to inform our actions today?

In partnership with a local art museum, students translated their arguments into visual and written advocacy through the creation of public-facing billboards. Each billboard communicated a clear claim about an issue students cared about, while accompanying writing explained the cause, why it mattered, and how historical figures inspired their call to action. The billboards functioned as both artistic expression and persuasive argument, demonstrating students’ ability to connect historical learning to contemporary social concerns.

As a culminating action, students developed advocacy plans centered on amplifying community voices and communicating their concerns to broader audiences. Through this process, students demonstrated an understanding that collective value requires not only recognizing the dignity and contributions of others, but also organizing thoughtfully to ensure that all voices are heard.

The Fifth Grade exhibition reflected students’ growing capacity to see themselves as advocates capable of contributing to community change. Through research, art, writing, and action, students demonstrated that collective value means working together to identify problems, elevate marginalized perspectives, and advocate for a more just and inclusive society.

Conclusion

Engaging in sustained, schoolwide study of the Black Lives Matter at School principles from early childhood through fifth grade allows students to develop a deep and evolving understanding of identity, community, justice, and collective responsibility. Rather than encountering these ideas briefly, students revisit them over time through inquiry, research, and interdisciplinary learning that culminates in Take Action Projects grounded in real community concerns.

These projects give students meaningful opportunities to apply their learning beyond the classroom, demonstrating that their voices and ideas can contribute to change. The Celebration of Learning serves as a critical part of this process, creating space for students to learn from one another across grade levels and experience themselves as part of a larger learning community.

Equally important is the intentional support provided to teachers as they engage in this work, ensuring that educators have the time, resources, and collaborative structures necessary to guide complex conversations and design authentic learning experiences. Together, this approach strengthens connections between students, their communities, and the real world, reinforcing the belief that education should prepare young people not only to understand society, but to actively participate in improving it.

Photos by Hampton Conway, Firebug Productions

Tamyka Morant, Ph.D, is an assistant principal at Bruce-Monroe at Park View, a Zinn Education Project Prentiss Charney Fellow, and a member of D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice.